Τελ Χαρίρι

Το Τελ Χαρίρι της Συρίας είναι η σημερινή ονομασία του αρχαίου Μάρι (σφηνοειδής γραφή: 𒈠𒌷𒆠, ma-riki, αραβική γλώσσα: تل حريري) που ανακαλύφθηκε το 1933 από τον Γάλλο αρχαιολόγο Αντρέ Παρρότ.[1] Βρίσκεται κοντά στο Αμπού Καμάλ και υπάγεται διοικητικά στο Ντέιρ αλ-Ζορ. Στην αρχαιολογική θέση του Μάρι έχουν αποκαλυφθεί αρχαιότητες που χρονολογούνται από το 3100 π.Χ. έως τον 7ο αιώνα μ.Χ.[2]

| Μάρι | |

|---|---|

| |

| 34°32′58″N 40°53′24″E | |

| Χώρα | Συρία |

| Διοικητική υπαγωγή | Abu Kamal |

| Έκταση | 600 σκάλα |

Ιστορία

ΕπεξεργασίαΤο πρώτο βασίλειο

ΕπεξεργασίαΔεν αποτελούσε έναν ασήμαντο οικισμό, ιδρύθηκε στην πρώιμη Δυναστική Περίοδο Α΄(2900 π.Χ.) με στόχο να ελέγξει το πλωτό εμπόριο του ποταμού Ευφράτη από την νότια Σουμερία προς το Λεβάντες στα βόρεια. Η πόλη δεν οικοδομήθηκε στις όχθες του Ευφράτη από φόβο πλημμύρας λόγω υπερχείλισης του ποταμού, οικίστηκε 7-10 χιλιόμετρα εσωτερικά και συνδέθηκε με τον ποταμό με μια πλωτή διώρυγα, τα ίχνη της δεν έχουν διασωθεί σήμερα.[3] Η ανασκαφή της αρχαιότερης πόλης ήταν πολύ δύσκολη, καλύφτηκε κάτω από πολλά νεότερα επίπεδα κατοίκησης.[4] Οι αρχαιολόγοι ανακάλυψαν ένα κυκλικό αντιπλημμυρικό φράγμα μήκους 300 μέτρων, είχε στόχο να προστατέψει τους κήπους και τις καλλιέργειες.[3] Ένα ισχυρό αμυντικό τείχος πλάτους 7 μέτρων και ύψους 10 μέτρων είχε κατασκευαστεί για την άμυνα της αρχαιότερης Μάρι, ενισχύθηκε με πολλούς αμυντικούς πύργους.[3][4] Άλλο ένα σημαντικό εύρημα ήταν ένας δρόμος που οδηγούσε από το κέντρο της πόλης μέχρι την πύλη εξόδου, περιβαλλόταν από τις κατοικίες.[4] Η Μάρι είχε έναν κεντρικό τύμβο ο οποίος δεν είχε την χρήση ανακτόρων ή ναού.[4][5] Μιά μεγάλη κατασκευή διαστάσεων 32 Χ 25 μέτρα φαίνεται ότι είχε διοικητική χρήση, περιείχε αίθουσες μήκους 12 μέτρων και πλάτους 6 μέτρων.[6] Η πόλη είχε εγκαταληφθεί στα τέλη της Πρώιμης Δυναστικής Περιόδου Β΄ για άγνωστους λόγους (2550 π.Χ.).[4]

Το δεύτερο βασίλειο

ΕπεξεργασίαΗ Μαρί οικοδομήθηκε και κατοικήθηκε ξανά στις αρχές της Πρώιμης Δυναστικής Περιόδου Γ΄ (2500 π.Χ.).[4][7][8] Η δεύτερη πόλη διατήρησε πολλά στοιχεία από την πρώτη όπως το εξωτερικό αμυντικό τείχος με την πύλη.[4][9] Διατήρησε επίσης τον εξωτερικό αμυντικό κυκλικό προμαχώνα, είχε διάμετρο 1.9 χιλιόμετρα, με ένα τείχος στην κορυφή ύψους δύο μέτρων ικανό να προστατέψει τους τοξότες.[4][9] Η αστική δομή της δεύτερης πόλης άλλαξε ωστόσο σημαντικά, οι νέοι δρόμοι και οι οικείες κατασκευάστηκαν με νέο σχέδιο ώστε να λειτουργεί καλύτερα η αποστράγγιση.[4] Στο κέντρο της πόλης βρέθηκαν αυτή την φορά ανάκτορα, είχαν επιπλέον και την χρήση ναού.[4] Στο οίκισμα βρέθηκαν τέσσερα διαδοχικά επίπεδα κατασκευής, τα δύο πρώτα αφορούσαν ναό αφιερωμένο σε άγνωστη θεότητα.[10][11] Τα δύο τελευταία που είχαν και την χρήση ανακτόρων οικοδομήθηκαν στην Ακκαδική περίοδο, είχε την αίθουσα του θρόνου και μια αίθουσα με τρεις διπλούς πίληνους στήλους που οδηγούσαν στον ναό.[10] Στην δεύτερη πόλη βρέθηκαν επίσης έξι μικρότεροι ναοί αφιερωμένοι σε θεότητες όπως η Ισταράτ, η Ιστάρ, ο Νινουρτά και ο Ούτου, όλες οι ναοί ήταν στο κέντρο της πόλης εκτός από αυτόν της Ινάννα.[11] Το δεύτερο βασίλειο είχε ένα πανίσχυρο αστικό διοικητικό κέντρο, ο βασιλείς της είχαν τον τίτλο του "Λουγκάλ".[7][12] Η σημαντικότερη πηγή ήταν μια επιστολή του βασιλιά Έννα-Νταγκάν (2350 π.Χ.) στον ομόλογο του βασιλιά της Έμπλα, απαριθμούσε τα κατορθώματα του ίδιου και των προκατόχων του.[13] Η επιστολή ωστόσο δεν έχει επιβεβαιωθεί, πολλοί ιστορικοί την αμφισβητούν.[14][15][16] Ο Έννα-Νταγκάν (περί το 2350 π.Χ.) δέχθηκε στην διάρκεια της βασιλείας του φόρο υποτέλειας από την Έμπλα, ηττήθηκε ωστόσο με αποτέλεσμα να λήξει η υποτέλεια.[17][18] Ο πόλεμος κλιμακώθηκε αργότερα αφού η Έμπλα συμμάχησε με την Κις και την Ναγκάρ, πέτυχαν νέα νίκη επί της Μαρί σε μάχη κοντά στην Τέκα.[19] Σε λίγα χρόνια ωστόσο μετά την νίκη της στην Τέκα η Έμπλα ηττήθηκε και καταστράφηκε από την Μάρι (περί το 2300 π.Χ.).[20]

Η Ακκαδική κατάκτηση

ΕπεξεργασίαΣε μερικές δεκαετίες μετά την καταστροφή της Έμπλα, ο ιδρυτής της Ακκαδικής αυτοκρατορίας Σαργών ο Μέγας κατέκτησε και κατέστρεψε και την ίδια την Μάρι.[21][22][23][24] O τελευταίος βασιλιάς της Μάρι πριν την Ακκαδική κατάκτηση ήταν ο Ισκί-Μάρι.[25] Ο Σαργών ο Μέγας καταγράφει στις επιτυχίες του το έτος που "κατέλαβε και κατέστρεψε την Μάρι", ο ιστορικός Μισέλ Αστούρ το τοποθετεί στο 2265 π.Χ.[24] Μετά την καταστροφή της η Μάρι έμεινε έρημη για δύο γενεές μέχρι που αποκαταστάθηκε από τον βασιλιά των Ακκάδων Μανιστουσού.[26] Οι Ακκάδιοι διόρισαν έναν "στρατιωτικό κυβερνήτη", εξακολουθούσαν να έχουν τον απόλυτο έλεγχο της πόλης, ο Ναράμ-Σιν διόρισε δύο από τις κόρες του αρχιέρειες σε ναούς της Μάρι.[27] Ο πρώτος "στρατιωτικός διοικητής" διορίστηκε από τους Ασσύριους (2266 π.Χ.), το αξίωμα έγινε κατόπιν κληρονομικό.[28][29]

Το τρίτο βασίλειο

ΕπεξεργασίαΗ αυτοκρατορία των Ακκάδων άρχισε να καταρρέει την εποχή του Σαρ-Καλί-Σαρί και η Μάρι κέρδισε την ανεξαρτησία της, η δυναστεία των "στρατιωτικών διοικητών" εξακολουθούσε να κυβερνάει την πόλη και όταν ανέβηκε στην εξουσία της Μεσοποταμίας η Τρίτη Δυναστεία της Ουρ.[30] Μια πριγκίπισσα από την Μάρι παντρεύτηκε έναν γιο του Ουρ-Ναμμού και η πόλη εξακολουθούσε να είναι υποτελής στην Ουρ.[31][32][33] Οι στρατιωτικοί διοικητές πήραν ωστόσο τον τίτλο του βασιλιά ως "Λουγκάλ", διεκδίκησαν την ανεξαρτησία τους από την αυλή της Ουρ, ένας από αυτούς ήταν και ο Πουζούρ Ιστάρ, σύγχρονος του Αμάρ-Σιν.[34][35] Η δυναστεία των "στρατιωτικών διοικητών" που είχαν τοποθετήσει οι Ακκάδες έληξε για άγνωστους λόγους, στην θέση της ανήλθε το δεύτερο μισό του 19ου αιώνα π.Χ. νέα δυναστεία.[36][37][38]

H δυναστεία των Λιμ

ΕπεξεργασίαΣτις αρχές της δεύτερης χιλιετίας π.Χ. η Εύφορη Ημισέληνος κατακλύστηκε από τους Αμορίτες που πήραν υπό την εξουσία τους και την Μάρι (1830 π.Χ.), ο Γιαγκίντ-Λιμ ίδρυσε την Αμορίτικη δυναστεία των Λιμ.[38][39] Τα αρχαιολογικά ευρήματα ωστόσο δείχνουν συνεχείς επαφές ανάμεσα στους Αμορίτες και στους επίσης Σημίτες προηγούμενους στρατιωτικούς διοικητές.[31] Ο Γιαγκίντ-Λιμ εξασφάλισε συμμαχία με την Εκαλαττούμ αλλά σύντομα συγκρούστηκαν και ξέσπασε μεταξύ τους πόλεμος.[40][41][42] Ο βασιλιάς της Εκαλλατούμ σύμφωνα με μια πινακίδα που βρέθηκε στην Μάρι συνέλαβε αιχμάλωτο τον γιο και διάδοχο του Γιαγκίντ-Λιμ Γιαχντούν-Λιμ, αργότερα ο Γιαγκίντ-Λιμ δολοφονήθηκε από τους υπηρέτες του.[40] Ο διάδοχος του Γιαχντούν-Λιμ πήρε τον τίτλο του βασιλιά της Μάρι (1820 π.Χ.).[42]

Στην αρχή της βασιλείας του υπέταξε επτά από τους αρχηγούς των επαναστατικών φυλών, οικοδόμησε ξανά τα τείχη της Μάρι και της Τέρκα με ένα κάστρο.[43] Ο Γιαχντούν-Λιμ απειλήθηκε με επιδρομές από Νομάδες με προέλευση από την Χαναάν, τους υπέταξε και τους ανάγκασε να πληρώσουν φόρο υποτέλειας, μετά την σύναψη ειρήνης οικοδόμησε ναό αφιερωμένο στον Ούτου. Επέκτεινε σημαντικά τα σύνορα του βασιλείου του προς τα δυτικά και έφτασε μέχρι την Μεσόγειο.[44][45] Αργότερα αντιμετώπισε μια εξέγερση με νομάδες από την Ράκκα, είχαν την στήριξη του Χαλεπίου που είχε ενοχληθεί από την συμμαχία του Γιαχντούν-Λιμ με την Εσνούννα.[34][44] Ο Γιαχντούν-Λιμ τους νίκησε αλλά απέφυγε έναν γενικότερο πόλεμο με το Χαλέπι.[46] Αντιμετώπισε ωστόσο την επιδρομή του πρώιμου βασιλιά της Ασσυρίας Σαμσί-Αντάντ Α΄, επίσης Αμορίτη, γιου του βασιλιά της Εκαλατούμ Ιλα Καμπκαμπού.[47] Δέχθηκε πολλές εκκλήσεις για βοήθεια από βασιλείς που απειλούσε ο Σαμσί-Αντάντ Α΄, πριν ωστόσο αναχωρήσει σε εκστρατεία δολοφονήθηκε από τον ίδιο τον γιο του Σουμού-Γιαμάμ, δολοφονήθηκε και ο ίδιος σε δύο χρόνια.[48][49] Ο ιστορικός Γουίλιαμ Τζέιμς Χάμπλιν λέει ωστόσο ότι ο Γιαχντούν-Λιμ έπεσε στην μάχη με τον Σαμσί-Αντάντ Α΄ (1796 π.Χ.), κατέλαβε κατόπιν την Μάρι και τοποθέτησε κυβερνήτη τον δεύτερο γιο του Γιασμάχ-Αντάντ.[50]

Ασσυριακή κυριαρχία

ΕπεξεργασίαΟ Γιασμάχ-Αντάντ παντρεύτηκε την κόρη του Γιαχντούν-Λιμ, η υπόλοιπη Οικογένεια Λιμ δραπέτευσε στο Χαλέπι.[51][52][53] Σε κάποια στιγμή με στόχο να εξασφαλίσει τις συμμαχίες του στην δυτική Συρία ο Σαμσί-Αντάντ Α΄ διέταξε τον γιο του να παντρευτεί την κόρη του βασιλιά της Κάτνας Ισί-Αντάντ Βελτούμ.[52] Ο Γιασμάχ-Αντάντ ήταν ωστόσο ήδη παντρεμένος με την κόρη του έκπτωτου βασιλιά, της συμπεριφέρθηκε υποτιμητικά σαν δεύτερη σύζυγο και της απαγόρευσε να ζει μαζί του στα ανάκτορα, αυτό προκάλεσε την οργή του πατέρα του.[52][54][55] Μετά τον θάνατο του Σαμσί-Αντάντ Α΄ (1776 π.Χ.) ο γιος ή εγγονός του Γιαχντούν-Λιμ Ζίμρι-Λιμ επέστρεψε από την εξορία, έδιωξε από την Μάρι τον ανίκανο Γιασμάχ-Αντάντ με την βοήθεια του βασιλιά του Χαλεπίου Γιαρίμ Λιμ Α΄.[56][57] Μετά την ενθρόνιση του ο Ζίμρι-Λιμ παντρεύτηκε την κόρη του βασιλιά του Χαλεπίου Γιαρίμ Λιμ Α΄ (1776 π.Χ.).[55] Η βοήθεια που παρείχε ο Γιαρίμ Λιμ Α΄ στον Ζίμρι Λιμ να ανακατακτήσει την Μάρι ενδυνάμωσε τις σχέσεις των δύο βασιλείων, ο Ζίμρι-Λιμ δήλωσε υπηρέτης του θεού Αδάδ.[58]

Αποκατάσταση των Λιμ

ΕπεξεργασίαO Ζίμρι-Λιμ ανέβηκε στον θρόνο δημιουργώντας ισχυρές συμμαχίες με την Εσνούννα και τον βασιλιά της Βαβυλώνας Χαμουραμπί, έστειλε τον στρατό του να βοηθήσει τους Βαβυλώνιους.[53][59] Ο νέος βασιλιάς επεκτάθηκε βόρεια του ποταμού Αβώρ όπου υπέταξε τα βασίλεια και τα έκανε φόρου υποτελή.[60][61][62] Η επέκταση συνεχίστηκε, ο Ζίμρι-Λιμ έφτασε μέχρι τις πεδιάδες της Νινευή και εξασφάλισε τον έλεγχο της περιοχής (1771 π.Χ.), το βασίλειο έγινε ένα μεγάλο εμπορικό κέντρο και μπήκε σε περίοδο ειρήνης.[55][63] Το μεγαλύτερο έργο του Ζιμρί-Λιμ ήταν η κατασκευή των βασιλικών ανακτόρων, έφτασαν μέχρι τα 275 δωμάτια με βασιλικά αρχεία και χιλιάδες πινακίδες.[64][65][66][67] Οι σχέσεις της Μάρι με την Βαβυλώνα χειροτέρευσαν κατά της διάρκεια μιας σύγκρουσης της Βαβυλώνας με το Ελάμ (1765 π.Χ.), ο Ζίμρι-Λιμ δεν έστειλε στον Χαμουραμπί την βοήθεια που του είχε υποσχεθεί ως σύμμαχος.[68] Στην μάχη που ακολούθησε ο Χαμουραμπί νίκησε τον Ζίμρι-Λιμ, διέλυσε την Μάρι, την ενσωματώθηκε στην αυτοκρατορία του και ανέτρεψε την δυναστεία των Λιμ (1761 π.Χ.).[69]

Ο Ζίμρι-Λιμ, βασίλευσε την περίοδο περίπου μεταξύ 1774-1762 π.Χ. και κατείχε σημαντική πολιτική επιρροή στην Εγγύς Ανατολή, καθιστώντας το βασίλειό του ιδιαίτερα πλούσιο. Με αυτά τα πλούτη μπόρεσε να οικοδομήσει το ασύγκριτο αυτό διαστάσεων και μεγαλείου παλάτι του.

Το ανάκτορο και οι πήλινες πινακίδες

ΕπεξεργασίαΑπό το ανάκτορο του βασιλιά Ζίμρι-Λιμ σώζονται σημαντικά αρχαιολογικά κατάλοιπα. Είναι διακοσμημένο με εξαίρετης τέχνης τοιχογραφίες.

Στο ανάκτορο αυτό βρέθηκε ένα εκτενές αρχείο πήλινων πινακίδων, που αποτελούν μία πολύτιμη πηγή γραπτών κειμένων της εποχής, γραμμένα στην Ακκαδική σφηνοειδή γραφή. Οι πινακίδες είναι στον αριθμό περισσότερες από 22.000, και βρέθηκαν κυρίως στο εσωτερικό του παλατιού και στην περιοχή γύρω από αυτό. Στην πλειοψηφία τους περιορίζονται χρονικά σε μία περίοδο 250 χρόνων περίπου, από την εποχή του Αμορίτη βασιλιά Γιασμάχ-Αντού (Yasmah-Addu) μέχρι την κατάκτηση του βασιλείου από τον Χαμμουραμπί (1761 π.Χ.). Περιέχουν διαφόρων ειδών πληροφορίες για το Μάρι. Είναι επιστολές, διοικητικά κείμενα, και λίγα κείμενα νομικού και θρησκευτικού περεχομένου. Αφορούν την καθημερινή ζωή, τις πολιτιστικές και εμπορικές δραστηριότητες, τις συμμαχίες και την γεμάτη διακυμάνσεις πολιτική και στρατιωτική τύχη του βασιλείου.

Από τις πινακίδες γίνονται γνωστές οι εμπορικές σχέσεις που ο Ζίμρι-Λιμ διατηρούσε με την Αλασία και το Καπτάρ. Κατά την εποχή αυτή, Αλασία ονομαζόταν η Κύπρος και Καπτάρ η Κρήτη. H Αλασία προμήθευε με χαλκό το Μάρι, ενώ το Καπτάρ προμήθευε το βασίλειο αυτό με αγγεία και άλλα αγαθά, αλλά προμηθευόταν από το Μάρι και πολύτιμες πρώτες ύλες όπως ο κασσίτερος, μία από τις περιοχές προέλευσης του οποίου ήταν το Αφγανιστάν.[70] Η Αλασία, όπως μας πληροφορούν τα αρχεία των πήλινων πινακίδων που έχουν βρεθεί στο Μάρι, καθώς και στην Αμάρνα και την Ουγκαρίτ, προμήθευε ήδη από τον 18ο αιώνα π.Χ. με χαλκό όχι μόνο το Μάρι αλλά και την Βαβυλωνία, ενώ στη διάρκεια του 15ου και του 14ου αιώνα μεγάλες ποσότητες χαλκού κατέφθαναν από το νησί της Κύπρου στην Αίγυπτο.[71] Σε άλλες πινακίδες που αποτελούν μέρος της βασιλικής αλληλογραφίας, αναφέρονται λέοντες οι οποίοι αιχμαλωτίζονται για να τους απελευθερώνουν έπειτα για τον βασιλιά, έτσι ώστε να μπορεί να τους σκοτώσει κυνηγώντας τους, καθώς ήταν σύμβολο δύναμης το κυνήγι άγριων ζώων. Χαρακτηριστικές σκηνές κυνηγιού απεικονίζονται στα μεταγενέστερα ασσυριακά ανάγλυφα που διακοσμούν το ανάκτορο του Ασσουρμπανιπάλ (7ος αιώνας π.Χ.) στη Νινευή.

Το τέλος του βασιλείου

ΕπεξεργασίαΠαρόλο που ο Ζίμρι-Λιμ με τον βασιλιά της Βαβυλωνίας, τον Χαμμουραμπί, ήταν σύμμαχοι, τελικά οι ανταγωνιστικές διαθέσεις του Χαμμουραμπί τον έκαναν να γίνει εχθρός του και να επιτεθεί κατά του Μάρι (1761 π.Χ.). Ο Χαμμουραμπί κατέστρεψε το παλάτι και τα τείχη της πόλης, και επέκτεινε τα όρια της επικυριαρχίας του στην περιοχή. Από τότε το Μάρι έχασε την δύναμή του και μεταφέρθηκε λίγο βορειότερα, στην Τέρκα.[72]

Εικόνες

Επεξεργασία-

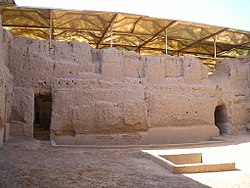

Το παλάτι του Ζίμρι-Λιμ όπως σώζεται σήμερα.

-

Τοιχογραφία από το παλάτι του Ζίμρι-Λιμ όπου απεικονίζεται φτερωτός λέοντας

-

Τοιχογραφία από το παλάτι του Ζίμρι-Λιμ που απεικονίζει τον ίδιο σε τελετή απονομής αξιώματος.

-

Το άγαλμα της θεάς με το αγγείο που αποτελούσε μέρος μίας κρήνης.

-

Πήλινη πινακίδα από το ανάκτορο του Ζίμρι-Λιμ στο Μάρι.

-

Επιγραφή από το άγαλμα του Ίντι-Ιλούμ σε σφηνοειδή γραφή που σημαίνει "Χώρα του Μάρι".

- Περισσότερα για το Μάρι στο Wikimedia Commons: Μάρι και Μουσείο Χαλεπίου.

Παραπομπές

Επεξεργασία- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (20-08-2020). André Parrot.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (07 Sept. 2010). Mari-ancient city, Syria.

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 3,2 Margueron 2013, σ. 520

- ↑ 4,00 4,01 4,02 4,03 4,04 4,05 4,06 4,07 4,08 4,09 Margueron 2003, σ. 136

- ↑ Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, σ. 286.

- ↑ Margueron 2013, σ. 522

- ↑ 7,0 7,1 Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, σ. 267

- ↑ Liverani 2013, σ. 117

- ↑ 9,0 9,1 Margueron 2013, σ. 523

- ↑ 10,0 10,1 Margueron 2003, σ. 137

- ↑ 11,0 11,1 Margueron 2013, σ. 527

- ↑ Nadali 2007, σ. 354

- ↑ Roux 1992, σ. 142

- ↑ Astour 2002, σ. 57

- ↑ Matthews & Benjamin 2006, σ. 261

- ↑ Liverani 2013, σ. 119

- ↑ Podany 2010, σ. 26

- ↑ Podany 2010, σ. 315

- ↑ Stieglitz 2002, σ. 219

- ↑ Bretschneider, Van Vyve & Leuven 2009, σ. 7

- ↑ https://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=sargon_year-names

- ↑ Potts, D. T. (2016). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. σσ. 92–93

- ↑ Álvarez-Mon, Javier; Basello, Gian Pietro; Wicks, Yasmina (2018). The Elamite World. Routledge. σ. 247

- ↑ 24,0 24,1 Astour 2002, σ. 75

- ↑ Bretschneider, Van Vyve & Leuven 2009, σ. 18

- ↑ Astour 2002, σσ. 71, 64

- ↑ Astour 2002, σ. 64

- ↑ Leick 2002, σ. 77

- ↑ Leick 2002, σ. 152

- ↑ Cooper 1999, σ. 65

- ↑ 31,0 31,1 Wossink 2009, σ. 31

- ↑ Tetlow 2004, σ. 10

- ↑ Bryce 2014, σ. 18

- ↑ 34,0 34,1 Bryce 2009, σ. 451

- ↑ Astour 2002, σ. 127, 132

- ↑ Roux 1992, σσ. 188, 189

- ↑ Frayne 1990, σ. 597

- ↑ 38,0 38,1 Astour 2002, σ. 139

- ↑ DeVries 2006, σ. 27

- ↑ 40,0 40,1 Porter 2012, σ. 31

- ↑ Frayne 1990, σ. 601.

- ↑ 42,0 42,1 Roux 1992, σ. 189

- ↑ Frayne 1990, σ. 603

- ↑ 44,0 44,1 Frayne 1990, σ. 606

- ↑ Fowden 2013, σ. 93

- ↑ Bryce 2014, σ. 19

- ↑ Pitard 2001, σ. 38

- ↑ Launderville 2003, σ. 271

- ↑ Frayne 1990, σ. 613

- ↑ William J. Hamblin (12 April 2006). Warfare in Ancient Near East. Taylor & Francis. σ. 170

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2011, σ. 109

- ↑ 52,0 52,1 52,2 Tetlow 2004, σ. 125

- ↑ 53,0 53,1 Bryce 2009, σ. 452

- ↑ Harris 2003, σ. 141

- ↑ 55,0 55,1 55,2 Hamblin 2006, σ. 258

- ↑ Liverani 2013, σ. 228

- ↑ Bryce 2014, σ. 20

- ↑ Malamat 1980, σ. 75

- ↑ Van Der Toorn 1996, σ. 101

- ↑ Kupper 1973, σ. 9

- ↑ Bryce 2009, σ. 329

- ↑ Bryce 2009, σ. 687

- ↑ Charpin 2012, σ. 39

- ↑ Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, σ. 286

- ↑ Burns 2009, σ. 198

- ↑ Gates 2003, σ. 65

- ↑ Shaw 1999, σ. 379

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2007, σ. 68

- ↑ Van De Mieroop 2007, σ. 70

- ↑ Heimpel, W. (2003)

- ↑ Knapp, B. (1985). JSTOR 12 (2): 231-250

- ↑ Mieroop, M. (2016)

Βιβλιογραφία

Επεξεργασία- Akkermans, Peter M. M. G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press.

- Archi, Alfonso; Biga, Maria Giovanna (2003). "A Victory over Mari and the Fall of Ebla". Journal of Cuneiform Studies.

- Armstrong, James A. (1996). "Sumer and Akkad". In Fagan, Brian M. (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press.

- Aruz, Joan; Wallenfels, Ronald, eds. (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Astour, Michael C. (2002). "A Reconstruction of the History of Ebla (Part 2)". In Gordon, Cyrus Herzl; Rendsburg, Gary (eds.). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language.

- Aubet, Maria Eugenia (2013). Commerce and Colonization in the Ancient Near East. Translated by Turton, Mary. Cambridge University Press.

- Bonatz, Dominik; Kühne, Hartmut; Mahmoud, Asʻad (1998). Rivers and Steppes: Cultural Heritage and Environment of the Syrian Jezireh: Catalogue to the Museum of Deir ez-Zor. Damascus: Ministry of Culture, Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums.

- Bretschneider, Joachim; Van Vyve, Anne-Sophie; Leuven, Greta Jans (2009). "War of the lords, The Battle of Chronology: Trying to Recognize Historical Iconography in the 3rd Millennium Glyptic Art in seals of Ishqi-Mari and from Beydar". Ugarit-Forschungen. Ugarit-Verlag. 41.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia. Routledge.

- Bryce, Trevor (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. Oxford University Press.

- Burns, Ross (2009) [1992]. Monuments of Syria: A Guide (revised ed.). I.B.Tauris.

- Charpin, Dominique (2011). "Patron and Client: Zimri-Lim and Asqudum the Diviner". In Radner, Karen; Robson, Eleanor (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. Oxford University Press.

- Charpin, Dominique (2012) [2003]. Hammurabi of Babylon. I.B.Tauris.

- Chavalas, Mark (2005). "The Age of Empires, 3100–900 BCE". In Snell, Daniel C. (ed.). A Companion to the Ancient Near East. Blackwell Publishing.

- Chew, Sing C. (2007). The Recurring Dark Ages: Ecological Stress, Climate Changes, and System Transformation. Trilogy on world ecological degradation. Vol. 2. Altamira Press.

- Cockburn, Patrick (February 11, 2014). "The Destruction of the Idols: Syria's Patrimony at Risk From Extremists". The Independent.

- Cohen, Mark E. (1993). The Cultic Calendars of the Ancient Near East. CDL Press: The University Press of Maryland.

- Cooper, Jerrold S (1999). "Sumerian and Semitic Writing in Most Ancient Syro-Mesopotamia". In van Lerberghe, Karel; Voet, Gabriela (eds.). Languages and Cultures in Contact: At the *Crossroads of Civilizations in the Syro-Mesopotamian realm. Proceedings of the 42th RAI. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta. Vol. 92. Peeters Publishers & Department of Oriental Studies, Leuven.

- Crawford, Harriet, ed. (2013). The Sumerian World. Routledge.

- Dalley, Stephanie (2002) [1984]. Mari and Karana, Two Old Babylonian Cities (2 ed.). Gorgias Press.

- Daniels, Brian I.; Hanson, Katryn (2015). "Archaeological Site Looting in Syria and Iraq: A Review of the Evidence". In Desmarais, France (ed.). Countering Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods: The Global Challenge of Protecting the World's Heritage. The International Council of Museums.

- Darke, Diana (2010) [2006]. Syria (2 ed.). Bradt Travel Guides.

- Deschaumes, Ghislaine Glasson; Butterlin, Pascal. "Face aux patrimoines culturels détruits du Proche-Orient ancien : défis de la reconstitution et de la restitution numériques".

- DeVries, LaMoine F. (2006). Cities of the Biblical World: An Introduction to the Archaeology, Geography, and History of Biblical Sites. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Dolce, Rita (2008). "Ebla before the Achievement of Palace G Culture: An Evaluation of the Early Syrian Archaic Period". In Kühne, Hartmut; Czichon, Rainer Maria; Kreppner, Florian Janoscha (eds.). Proceedings of the 4th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 29 March - 3 April 2004, Freie Universität Berlin. Vol. 2. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Dougherty, Beth K.; Ghareeb, Edmund A. (2013). Woronoff, Jon (ed.). Historical Dictionary of Iraq. Historical Dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East (2 ed.). Scarecrow Press.

- Evans, Jean M. (2012). The Lives of Sumerian Sculpture: An Archaeology of the Early Dynastic Temple. Cambridge University Press.

- Feliu, Lluís (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria. Translated by Watson, Wilfred GE. Brill.

- Finer, Samuel Edward (1997). Ancient monarchies and empires. The History of Government from the Earliest Times. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press.

- Fleming, Daniel E. (2004). "Prophets and Temple Personnel in the Mari Archives". In Grabbe, Lester L.; Bellis, Alice Ogden (eds.). The Priests in the Prophets: The Portrayal of Priests, Prophets, and Other Religious Specialists in the Latter Prophets. T&T Clark International.

- Fleming, Daniel E. (2012). The Legacy of Israel in Judah's Bible: History, Politics, and the Reinscribing of Tradition. Cambridge University Press.

- Fowden, Garth (2014). Before and After Muhammad: The First Millennium Refocused. Princeton University Press.

- Frayne, Douglas (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003–1595 BC). The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia Early Periods. Vol. 4.

- Frayne, Douglas (2001). "In Abraham's Footsteps". In Daviau, Paulette Maria Michèle; Wevers, John W.; Weigl, Michael (eds.). The World of the Aramaeans: Biblical Studies in Honour of Paul-Eugène Dion. Vol. 1. Sheffield Academic.

- Frayne, Douglas (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods (2700–2350 BC). The Royal inscriptions of Mesopotamia Early Periods. Vol. 1. University of Toronto Press.

- Gadd, Cyril John (1971). "The Cities of Babylonia". In Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen; Gadd, Cyril John; Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (eds.). Part 2: Early History of the Middle East. The Cambridge Ancient History (Second Revised Series). Vol. 1 (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Gates, Charles (2003). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Routledge.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). "Introduction and Overview". In Grabbe, Lester L.; Bellis, Alice Ogden (eds.). The Priests in the Prophets: The Portrayal of Priests, Prophets, and Other Religious Specialists in the Latter Prophets. T&T Clark International.

- Grayson, Albert Kirk (1972). Assyrian Royal Inscriptions: From the Beginning to Ashur-Resha-Ishi I. Records of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 1. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Green, Alberto Ravinell Whitney (2003). The Storm-god in the Ancient Near East. Biblical and Judaic studies from the University of California, San Diego. Vol. 8. Eisenbrauns.

- Haldar, Alfred (1971). Who Were the Amorites?. Monographs on the ancient Near East. Vol. 1. Brill.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. Routledge.

- Harris, Rivkah (2003) [2000]. Gender and Aging in Mesopotamia: The Gilgamesh Epic and Other Ancient Literature. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Hasselbach, Rebecca (2005). Sargonic Akkadian: A Historical and Comparative Study of the Syllabic Texts. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Heimpel, Wolfgang (2003). Letters to the King of Mari: A New Translation, with Historical Introduction, Notes, and Commentary. Mesopotamian civilizations. Vol. 12. Eisenbrauns.

- Heintz, Jean Georges; Bodi, Daniel; Millot, Lison (1990). Bibliographie de Mari: Archéologie et Textes (1933–1988). Travaux du Groupe de Recherches et d'Études Sémitiques Anciennes (G.R.E.S.A.), Université des Sciences Humaines de Strasbourg (in French). Vol. 3. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (2010) [1963]. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press.

- Kupper, Jean Robert (1973). "Northern Mesopotamia and Syria". In Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen; Gadd, Cyril John; Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière; Sollberger, Edmond (eds.). Part 1: The Middle East and the Aegean Region, c.1800–1380 BC. The Cambridge Ancient History (Second Revised Series). Vol. 2 (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Larsen, Mogens Trolle (2008). "The Middle Bronze Age". In Aruz, Joan; Benzel, Kim; Evans, Jean M. (eds.). Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C.. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Launderville, Dale (2003). Piety and Politics: The Dynamics of Royal Authority in Homeric Greece, Biblical Israel, and Old Babylonian Mesopotamia. William B. Eerdmans Publishing.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2002). Who's Who in the Ancient Near East. Routledge.

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge.

- Maisels, Charles Keith (2005) [1990]. The Emergence of Civilisation: From Hunting and Gathering to Agriculture, Cities and the State of the Near East. Routledge.

- Malamat, Abraham (1980). "A Mari Prophecy and Nathan's Dynastic Oracle". In Emerton, John Adney (ed.). Prophecy: Essays presented to Georg Fohrer on his Sixty-Fifth Birthday. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. Vol. CL. Walter de Gruyter.

- Malamat, Abraham (1998). Mari and the Bible. Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 12. Brill.

- Margueron, Jean-Claude (1992). "The 1979–1982 Excavations at Mari: New Perspectives and Results". In Young, Gordon Douglas (ed.). Mari in Retrospect: Fifty Years of Mari and Mari Studies. Eisenbrauns.

- Margueron, Jean-Claude (2003). "Mari and the Syro-Mesopotamian World". In Aruz, Joan; Wallenfels, Ronald (eds.). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Margueron, Jean-Claude (2013). "The Kingdom of Mari". In Crawford, Harriet (ed.). The Sumerian World. Translated by Crawford, Harriet. Routledge.

- Matthews, Victor Harold; Benjamin, Don C. (2006) [1994]. Old Testament Parallels: Laws and Stories from the Ancient Near East (3 ed.). Paulist Press.

- Matthiae, Paolo (2003). "Ebla and the Early Urbanization of Syria". In Aruz, Joan; Wallenfels, Ronald (eds.). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- McLerran, Dan (September 13, 2011). "Ancient Mesopotamian City in Need of Rescue". Popular Archaeology Magazine. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- McMahon, Augusta (2013). "North Mesopotamia in the Third Millennium BC". In Crawford, Harriet (ed.). The Sumerian World. Routledge.

- Michalowski, Piotr (1993). "Memory and Deed: The Historiography of the Political Expansion of the Akkad State". In Liverani, Mario (ed.). Akkad: the First World Empire: Structure, Ideology, Traditions. History of the Ancient Near East Studies. Vol. 5. Padua: S.a.r.g.o.n. Editrice Libreria.

- Michalowski, Piotr (2000). "Amorites". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans Publishing.

- Michalowski, Piotr (2003). "The Earliest Scholastic Tradition". In Aruz, Joan; Wallenfels, Ronald (eds.). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Nadali, Davide (2007). "Monuments of War, War of Monuments: Some Considerations on Commemorating War in the Third Millennium BC". Orientalia. Pontificium Institutum Biblicum. 76 (4).

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Daily Life Through History. Greenwood Press.

- Nissinen, Martti; Seow, Choon Leong; Ritner, Robert Kriech (2003). Machinist, Peter (ed.). Prophets and Prophecy in the Ancient Near East. Writings from the Ancient World. Vol. 12. Society of Biblical Literature. Atlanta.

- Ochterbeek, Cynthia (1996). "Dan". In Berney, Kathryn Ann; Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Hudson, Christopher; La Boda, Sharon (eds.). Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Vol. 4. Routledge.

- Oldenburg, Ulf (1969). The Conflict between El and Ba'al in Canaanite Religion. Dissertationes ad Historiam Religionum Pertinentes. Vol. 3. Brill.

- Oliva, Juan (2008). Textos Para Una Historia Política de Siria-Palestina I (in Spanish). Ediciones Akal.

- Otto, Adelheid; Biga, Maria Giovanna (2010). "Thoughts About the Identification of Tall Bazi with Armi of the Ebla Texts". In Matthiae, Paolo; Pinnock, Frances; Nigro, Lorenzo; Marchetti, Nicolò; Romano, Licia (eds.). Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East: Near Eastern archaeology in the past, present and future: heritage and identity, ethnoarchaeological and interdisciplinary approach, results and perspectives; visual expression and craft production in the definition of social relations and status. Vol. 1. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Pardee, Dennis; Glass, Jonathan T. (1984). "Literary Sources for the History of Palestine and Syria: The Mari Archives". The Biblical Archaeologist. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 47 (2).

- Pettinato, Giovanni (1981). The archives of Ebla: an empire inscribed in clay. Doubleday.

- Pitard, Wayne T. (2001) [1998]. "Before Israel: Syria-Palestine in the Bronze Age". In Coogan, Michael David (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World (revised ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Podany, Amanda H. (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press.

- Porter, Anne (2012). Mobile Pastoralism and the Formation of Near Eastern Civilizations: Weaving Together Society. Cambridge University Press.

- Riehl, Simone; Pustovoytov, Konstantin; Dornauer, Aron; Sallaberger, Walther (2013). "Mid-to-Late Holocene Agricultural System Transformations in the Northern Fertile Crescent: A Review of the Archaeobotanical, Geoarchaeological, and Philological Evidence". In Giosan, Liviu; Fuller, Dorian Q.; Nicoll, Kathleen; Flad, Rowan K.; Clift, Peter D. (eds.). Climates, Landscapes, and Civilizations. Geophysical Monograph Series. Vol. IICC. American Geophysical Union.

- Roux, Georges (1992) [1964]. Ancient Iraq (3 ed.). Penguin Putnam.

- Shaw, Ian (1999). "Mari". In Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert (eds.). A Dictionary of Archaeology. John Wiley & Sons.

- Sicker, Martin (2000). The Pre-Islamic Middle East. Praeger.

- Simons, Marlise (December 31, 2016). "Damaged by War, Syria's Cultural Sites Rise Anew in France". The New York Times. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- Smith, Mark S. (1995). "The God Athtar in the Ancient Near East and His Place in KTU 1.6 I". In Zevit, Ziony; Gitin, Seymour; Sokoloff, Michael (eds.). Solving Riddles and Untying Knots: Biblical, Epigraphic, and Semitic Studies in Honor of Jonas C. Greenfield. Eisenbrauns.

- Stieglitz, Robert R. (2002). "The Deified Kings of Ebla". In Gordon, Cyrus Herzl; Rendsburg, Gary (eds.). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language. Vol. 4. Eisenbrauns.

- Strommenger, Eva (1964) [1962]. 5000 Years of the Art of Mesopotamia. Translated by Haglund, Christina. Harry N. Abrams.

- Suriano, Matthew J. (2010). The Politics of Dead Kings: Dynastic Ancestors in the Book of Kings and Ancient Israel. Forschungen zum Alten Testament. Vol. 48. Mohr Siebeck.

- Teissier, Beatrice (1996) [1995]. Egyptian Iconography on Syro-Palestinian Cylinder Seals of the Middle Bronze Age. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis- Series Archaeologica. Vol. 11. University Press Fribourg Switzerland.

- Tetlow, Elisabeth Meier (2004). Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: The Ancient Near East. Vol. 1. Continuum.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (2007). "A Testimony of the Good King: Reading the Mesha Stela". In Grabbe, Lester L. (ed.). Ahab Agonistes: The Rise and Fall of the Omri Dynasty. T&T Clark International.

- Tinney, Steve; Novotny, Jamie; Robson, Eleanor; Veldhuis, Niek, eds. (2020). "Mari [1] (SN)". Oracc (Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus). Oracc Steering Committee.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (2002). "Foreign Contacts and the Rise of an Elite in Early Dynastic Babylonia". In Ehrenberg, Erica (ed.). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. Eisenbrauns.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (2007) [2005]. King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. Blackwell Ancient Lives. Vol. 19. Blackwell Publishing.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (2011) [2003]. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000 - 323 BC. Blackwell History of the Ancient World. Vol. 6 (2 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-2709-0.

- Van Der Meer, Petrus (1955) [1947]. The Chronology of Ancient Western Asia and Egypt. Documenta et Monumenta Orientis Antiqui. Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Brill.

- Van Der Toorn, Karel (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Ugarit and Israel: Continuity and Changes in the Forms of Religious Life. Studies in the History of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 7. Brill.

- Viollet, Pierre-Louis (2007) [2005]. Water Engineering in Ancient Civilizations: 5,000 Years of History. IAHR Monographs. Vol. 7. Translated by Holly, Forrest M. CRC Press.

- Walton, John H. (1990) [1989]. Ancient Israelite Literature in Its Cultural Context: A Survey of Parallels Between Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Zondervan Publishing House.

- Wossink, Arne (2009). Challenging Climate Change: Competition and Cooperation Among Pastoralists and Agriculturalists in Northern Mesopotamia (c. 3000–1600 BC). Sidestone Press.

Εξωτερικοί σύνδεσμοι

Επεξεργασία- UNESCO. Observatory of Syrian Cultural Heritage. Mari (Tell Hariri) (To Mάρι, Μνημείο Παγκόσμιας Πολιτιστικής Κληρονομιάς).

- Jean-Claude Margueron - Mari (Οι ανασκαφές των Γάλλων στο Μάρι). Archeologie Culture France.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (07 Sept. 2010). Mari-ancient city, Syria. Publisher: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (20 Aug. 2020). André Parrot French archaeologist.Publisher: Encyclopædia Britannica.